In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

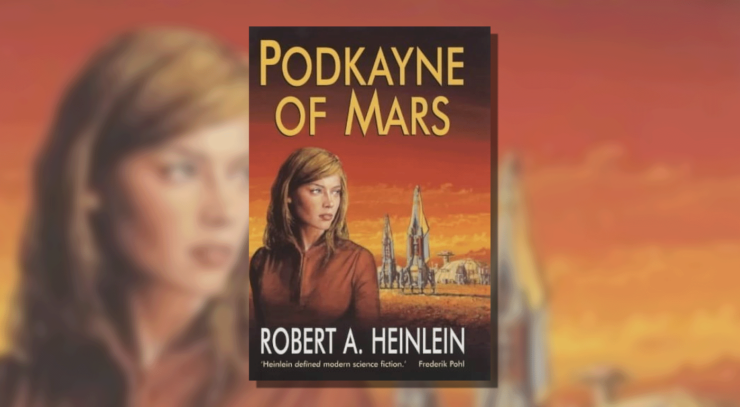

Podkayne of Mars is far from Robert Heinlein’s worst book, but it is definitely one of his less successful efforts. The tale reads like one of his juveniles—albeit one with a rare female protagonist—but Heinlein grafts on a moral targeted squarely at adults. Then there’s the fact that Heinlein’s original ending was disliked by the editors to whom he was pitching the story. The result of all this dissonance is a tale that has some entertaining parts, but ends up being a mishmash of disparate elements.

Heinlein had originally intended the book as kind of a travelogue, following a young girl in her travels around the solar system, and he created one of his most appealing characters in young Podkayne Fries. Perhaps if he had stuck with his original vision, he would have produced a charming, feminine counterpart to the popular juvenile series he had written for boys. On the other hand, some elements of the future society he’s depicting simply don’t work—while his settings often felt real and lived-in, his portrayal of life on a space liner in this book feels downright reactionary, and the future he envisions reflects attitudes, especially regarding women’s roles, which were already changing when the story was being written.

After much of the book was completed, Heinlein grafted on elements that changed the entire tone of the work. When his editors asked for changes, the normally astute Heinlein seemed baffled by their resistance to his artistic vision. Ultimately, the problems with this novel went far deeper than the relatively minor changes he made in order to satisfy their criticism.

About the Author

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) was one of America’s most celebrated science fiction authors, frequently referred to as the Dean of Science Fiction. I have often reviewed his work in this column, including Starship Troopers, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, “Destination Moon” (contained in the collection Three Times Infinity), The Pursuit of the Pankera/The Number of the Beast, and Glory Road. From 1947 to 1958, he also wrote a series of a dozen juvenile novels for Charles Scribner’s Sons, a firm interested in publishing science fiction novels targeted at young boys. These novels include a wide variety of tales, and contain some of Heinlein’s best work (you can follow the links to my reviews of each title): Rocket Ship Galileo, Space Cadet, Red Planet, Farmer in the Sky, Between Planets, The Rolling Stones, Starman Jones, The Star Beast, Tunnel in the Sky, Time for the Stars, Citizen of the Galaxy, and Have Spacesuit Will Travel.

Podkayne of Mars

Podkayne Fries is a child of privilege on a newly independent Mars, a young woman on the cusp of adulthood, who dreams of someday being a spaceship captain. Her father, a noted historian, lost an arm in the struggle for independence, and her great-uncle Tom, a Senator-at-Large in the Martian government, was another hero of the rebellion. Her mother is a prominent engineer who oversaw the transformation of Mars’ moons, Deimos and Phobos, into commercial spaceports. The one dim spot in Poddy’s life is her irritating younger brother, Clark, who is smarter than her and just about everyone around him, and is dedicated to using that brainpower to make Poddy miserable.

The book takes the form of first-person entries from Poddy’s diary, although there are also occasional entries Clark has made in invisible ink—her diary is not as private as she thinks, and he delights in leaving his mark in it. Heinlein has a breezy prose style that makes the book flow smoothly, although occasionally some of Poddy’s observations feel less like a young woman’s reflections and more like something an older man might think…

Poddy has dreamed of visiting Earth all her life, but just as the whole family is ready to leave on a trip to the homeworld, disaster strikes. Mars has a eugenics program, and as members of the planetary elite, her parents are obligated to have five children. The youngest three were frozen, to be decanted and raised at a time convenient to the family, but an administrative error has resulted in their untimely birth, and now her parents have their hands full with three new babies and are unable to travel. But good old Uncle Tom not only agrees to take Poddy and Clark on their trip, but he convinces the Marsopolis Creche to pay for the voyage as reparations for their mistake, and they get a berth on a liner going to Venus on its way to Earth (two planets instead of just one!). They happily depart, although Poddy finds her luggage three kilos heavier than she thought, and Clark pitches a fit at customs that causes him to go through an invasive search. Uncle Tom’s political status allows him and Poddy to breeze through without a second glance, and Clark eventually joins them. The liner they are boarding, Tricorn, is a modern ship that voyages at constant boost, even better than the one they were originally scheduled to ride.

While Heinlein’s predictive abilities result in some convincing aspects of Mars society (he even has a character using a portable pocket telephone at one point), he fails in some important ways. His society is still thoroughly rooted in the 1950s. It is male-dominated, with Poddy’s mother being a rare exception to the status quo. And the customs and service aboard the liner are the same as one would find aboard an Earth-bound ocean liner in the days before passenger airplanes made that mode of travel obsolete. There are formal dinners and dances, and a very stratified society divided by passenger classes. Poddy charms her way into nearly unlimited access to the control room, but finds to her dismay that astrogation involves lots of tough math, and command decisions can be very stressful. She meets “Girdie,” a newly divorced socialite who is returning to Earth. Poddy is also befriended by a matronly old woman, who starts treating her like a servant, and accuses Poddy of putting on airs when she stands up for herself. Poddy then overhears the woman gossiping about Poddy’s mixed heritage, and we find Uncle Tom’s side of the family is of Māori descent (Heinlein might have thought naming a person of color “Uncle Tom” was funny, but I didn’t).

Poddy discovers that Clark hid an object in her luggage that he was paid to smuggle aboard the ship—a miniature nuclear device. Clark assures her he disarmed the bomb, but is hanging on to it in case he needs it (!?!). And here we begin to see Clark portrayed as not just an irritating little brother, but a flat-out sociopath. There is a solar storm that requires everyone aboard Tricorn to take shelter in the center of the ship, where Poddy and Girdie are pressed into service to help take care of infants. Poddy realizes she enjoys taking care of babies, perhaps more than she might enjoy being a spaceship officer.

When they reach Venus, they find a hyper-commercialized culture where everything is a commodity. It turns out that Girdie’s ex-husband had lost all her money, and she has decided Venus is the best place for her to regain a fortune, so she takes a job in one of the casinos. Uncle Tom spends a lot of time with the Chairman of Venus while Poddy is wined and dined by the Chairman’s son. But then Clark is kidnapped, and it turns out Uncle Tom’s vacation with the kids is really a cover for a secret diplomatic mission. Poddy finds clues to where Clark might be and follows them, but finds herself captured as well, only to discover that Uncle Tom is also a captive. The woman behind the plot, someone they barely noticed on their voyage, lets Tom go, keeping Poddy and Clark as leverage to ensure Tom’s compliance in undermining his upcoming political negotiations. Poddy is threatened with being put in a cage with a brutal Venusian creature, and is harassed by a tiny, semi-intelligent Venusian “fairy.” But Clark kills the woman, arms his nuclear weapon on a timer to destroy her safe house (how he managed to hide that weapon during his capture is left as an exercise for the reader), and he and Poddy head out separately toward safety.

Dueling Endings (Spoilers Ahead)

When Podkayne of Mars was originally published, it ended with a postlude revealing that while Clark escaped the nuclear blast that destroyed the safe house, Podkayne had circled back to rescue the Venusian fairy in the house, and was in critical condition. Her Uncle Tom calls Poddy’s mother and blames her for her daughter’s misfortune, insisting it was her lack of maternal parenting that had led to the incident. But with the 1989 publication of a posthumous collection of Heinlein’s letters, Grumbles from the Grave, the world learned that the published postlude had replaced the version where Poddy died, an ending Heinlein preferred.

While I was preparing this review, the Heinlein Society serendipitously posted on Facebook an excerpt from William H. Patterson Jr’s two-volume biography, Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue with His Century, which discussed the controversy over the ending of Podkayne of Mars. It revealed that Heinlein did not consider the book a juvenile, and also that he considered its main message that women should devote themselves to raising their children rather than trying to pursue a career. That can be seen in Podkayne’s growing realization that she preferred caring for infants over navigating a spaceship. Clark’s maladjustment and lack of empathy was also meant as an indictment of his mother’s decision to pursue a career—he’s a living example of the risks of ignoring a child, with only the trauma of losing his sister being able to penetrate his selfish worldview.

When Jim Baen obtained the rights to a number of Heinlein books in the early 1990s, he decided to generate some attention for his 1993 reprint of Podkayne of Mars by releasing a trade paperback version with both endings and holding an essay contest to see which readers preferred. And he was stunned not only at the volume of responses, but by the passion of the essays.

Not having a copy of Podkayne of Mars on my shelves, I bought that trade paperback when it was published. Seeing the contest, I suggested to my then-15-year-old son, Alan Junior, that we both read the book and prepare an essay. He agreed, and it turned out our votes cancelled each other out. With his Gen X practicality, he pointed out Heinlein’s original ending was the only one that logically flowed from the rest of the book, as it was improbable for Poddy to have survived the nuclear blast. I myself, being a bit more romantic, argued it was unfair for Heinlein to have written what appeared to be a juvenile, luring readers into empathizing with Poddy, only to kill her off as an object lesson for her brother, grafting a moral for adults onto a book for youngsters. Both of our essays were among those printed in the mass market paperback edition in 1995. Overall, the majority of essays supported future editions of the book appearing with Heinlein’s preferred ending.

It was a few years later that I found a term that put my misgivings about Podkayne of Mars into focus, and that term was “fridging.” Coined by Gail Simone in 1999, most of you will be very familiar with the “women in refrigerators” trope, in which violence towards female characters is used as a plot device to motivate the actions and emotional responses of male characters. That term certainly fits Heinlein’s original vision for Podkayne of Mars to a T. He had no problem sacrificing the viewpoint character of his book as an object lesson for her younger brother. And I have a feeling, had Baen’s contest and the debate about the ending been held after the critical discussion over fridging had permeated popular culture, popular opinion might have taken a different direction.

Final Thoughts

I remembered Podkayne of Mars fondly from my youth, largely because Poddy was such an appealing character, although I disliked the gloomy ending with her suffering grievous injuries (it was only later I found out how much more gloomy that ending could have been). Re-reading it for the Baen contest, I primarily focused on the ending, and the pros and cons of changing it. But reading the book again for this column, I found myself disliking it throughout. The “women belong in the home” theme was already becoming dated when Heinlein wrote the book, and now I find it downright offensive. I began to imagine what I would have recommended as changes, edits which would have started long before the ending. I would have suggested that Heinlein go back to stressing the same virtues of bravery, determination, and character that made his earlier juveniles so successful. I would have urged him to drop the “secret nuke” sub-plot, which painted Clark as so antisocial and arrogant he was more a prop than a realistic character. The theme of character growth could have been shown by Poddy and Clark learning to work together and respect each other during their escape on Venus, and by giving them the opportunity to see the world that exists outside their privileged bubble during their struggles in the wilds and among poor settlers. I definitely would have urged Heinlein to drop his insistence on shoehorning a cautionary tale about childrearing into a coming-of-age adventure story, a choice I think was tone-deaf at best.

And now that you’ve heard my opinions on the book, I turn the floor over to you. What are your thoughts on Podkayne of Mars? If you were Heinlein’s editor, reading it for the first time, would you have accepted his work without revision—and if not, what changes would you have suggested? And since Heinlein failed in his attempt to write a juvenile science fiction adventure with a female protagonist, can you recommend books that have done that successfully?

Good analysis. Heinlein was usually reasonably good with female characters (comparatively and for the time) so the clunkiness of this stands out badly. I still remember getting to the part where she thinks she likes babies better than a career and how clunkily sexist that felt.

Heinlein had been putting portable phones in his stories since at least 1947. The sentence “She opened her purse and snatched out her telephone” comes from the story “Jerry Was a Man.”

This was a “read once” for me, a long time ago. But I do recall Clark as being fairly realistic, or at least a type of person I knew…

Society being highly stratified seems to have aged better than I would have hoped.

I read this once many years ago. I remember being confused by the ending, probably by the shift from Podkayne as the main character. I don’t remember noticing the sexism but it was an unexamined assumption in most of the books I read in those days. Girls could go have adventures as long as they deferred to the boys’ leadership and managed the domestic side of things. (Not universal, but very common.) I am sorry the book didn’t follow through on its original premise of Podkayne having adventures. I would reread that one, as I occasionally reread and enjoy Space Cadet and Have Spacesuit, Will Travel. But I don’t want to reread this one, with either ending.

My first thought on your essay is that comparing a trans-Atlantic flight to a non-Relativistic flight between planets is not a good comparison. Much of the formal dinners and dances on ocean liners existed because ship travel is long and tedious. (My mother and her family went to Greece by freighter, which was long and tedious without the distractions of formal dinners and dances. On the other hand, she learned to play bridge when the entire trip consisted of her parents playing against the captain and herself.)

As for the class based system, it’s interesting to see that the class based system is coming back on the newer massive cruisers, with well-healed passengers getting their own lounges, dining areas, and even ships within ships so they don’t have to mix with the hoi-polloi.

I hadn’t thought about the old customs of ocean travel re-emerging on the long voyages between planets. Because they are being kept alive on cruise ships, that might actually happen. Thanks for that observation!

It’s worth noting that Heinlein wrote Podkayne about 7 years after the voyages he and Ginny took, documented in Tramp Royale (1953-1954, Podkayne was submitted in 1962 and published in ’63)

I read this when I was a wee teenager. My memories of it seem to be better than the reality.

Heinlein was probably better with female characters than most of his male contemporaries, but that’s a very low bar to cross. I’d tend to dispute the idea that Heinlein was particularly good with female characters, even later in his work.

I think I last read this around ten or fifteen years ago as part of a re-read of Heinlein’s juveniles. I had either Podkayne or Starship Troopers as the end point.

My favourite part of Podkayne is how she is part of a much, much larger plot but she largely doesn’t notice because at her age she’d rather chase a boy.

My takeaway at the time wasn’t that women should stick to women’s work, but that they should be allowed to choose it if they wanted to. And to choose a career where you had the talent or could develop the skills and not chase a dream you were unsuited to.

I do agree that Clark tips way too far over into sociopathy and the message about Poddy’s mother spending too much time at work is tiresomely Heinleinian.

This was my favorite book when I was a tween (mid-70s). I identified strongly with Podkayne, disliked her brother—who I thought I was intended to identify with—and basically I just disregarded the end. I didn’t see the sexism at the time; on the contrary, to my mind it gave me a smart, capable girl as the protagonist. That’s completely how I read Heinlein. I know that’s weird.

But I think that the culture I was in was much more regressive than Heinlein, so I just assumed his portrayal of smart women was intended to be antisexist. Likewise with what I interpreted as sex-positvity. I didn’t really see the (big) problems with Heinlein; he was less sexist and more sex-positive than anyone else I was reading at the time and this was, what, fifteen years after Podkayne’s publication? I stopped reading children’s books at 9yo, and what was available to me was whatever my parents were reading. This was the time when SiaSL was considered outre and my dad bought about a dozen Heinlein books after reading it, some juveniles and some not. He wasn’t a SF reader. He mostly read spy novels and my mom read horror. So my reading material was very pulpy and Heinlein’s creepiness wasn’t so glaring in that context.

My feelings and thoughts about Heinlein are weird and very ambivalent and it’s always strange to me to read discussions of his work. It meant something to me that was, honestly, the opposite of how his books strike most people.

The lesson I’ve taken from that is that mere representation is by itself very influential for young readers. Podkayne very well may have been the first book I read with a girl protagonist (I’m male). I really liked her! And I very strongly identified with her, possibly more than any other book character I’d read at the time. I *still* identify with the version of her that lives in my memory. Make of that as you will.

Jack Williamson lived a few blocks from me, but I read Heinlein even before him.

Did you ever get a chance to read Heinlein’s The Menace From Earth? The protagonist of that story, Holly, is an aspiring teen starship designer, and in an inversion from Podkayne her boyfriend is the one who is distracted from their dream of running an engineering company when he seemingly develops a crush on an older woman.

Like Poddy, Holly is also smart, brave and resourceful. But she seems gifted enough in her field to actually make it in a “man’s world”.